Unlike Omaha Beach, where almost all remnants of the D-Day battle of World War II have been removed, the spit of cliff called Pointe du Hoc looks much as it must have right after the Normandy landings of June 6, 1944. Of course, all the guns and explosives have been removed, but the evidence of the violence is evident in the shattered remains of the German fortifications.

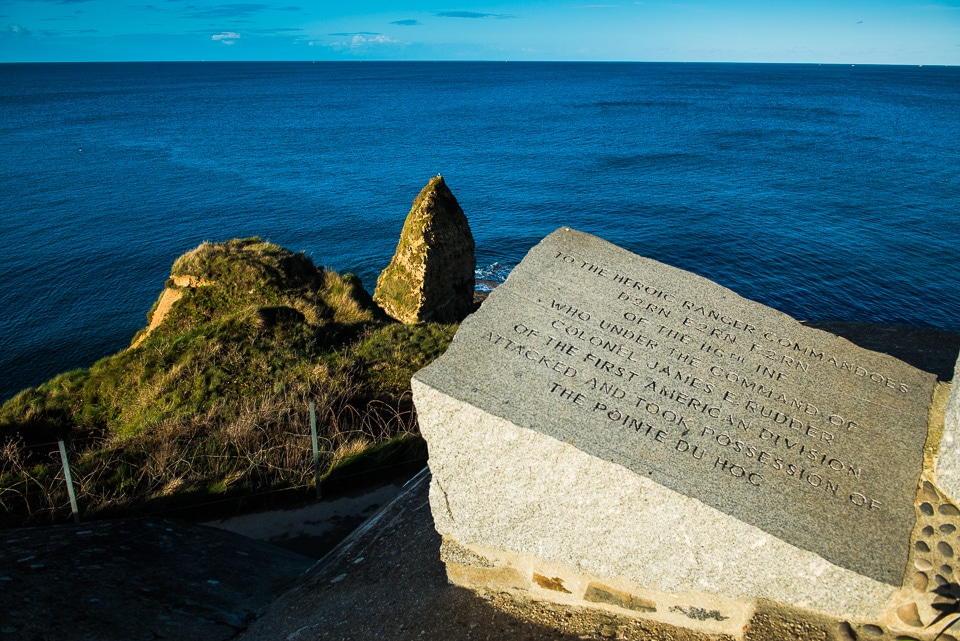

Pointe du Hoc was a key part of Hitler's Atlantic Wall. It is a sheer cliff about 100 feet high which the Germans had outfitted with large 155 mm guns that could direct fire down on both Omaha and Utah beaches. The US 2nd Ranger Battalion, under the command of Lt. Colonel James E. Rudder, had the job on D-Day morning of scaling those cliffs to knock out the guns that could wreak havoc on the American troops landing at both beaches. Companies of the 5th Ranger Battalion, of which my father was a member, waited in landing craft just off the beach. They were to land and continue the attack if the 2nd Rangers failed.

Before D-Day, the Allies pummeled Pointe Du Hoc with artillery from both from the air and the sea, destroying some of the German fortifications. Nevertheless, they feared the German guns were still operational, and so sent in the Rangers.

The day of the landings the gun emplacements were bombarded again, but because the landing craft carrying the Army Rangers were subjected to unexpected choppy seas and a strong current, they arrived at Pointe du Hoc nearly 40 minutes after the predicted time. The bombardment had stopped those 40 minutes earlier, and so the Germans had time to reoccupy their positions to repel the Rangers.

The 2nd Rangers suffered horrible casualties but did succeed in scaling the cliffs and capturing Pointe du Hoc. But, as it often happens in war, intelligence was outdated. The Germans had moved the guns to a wood a kilometer behind the cliff, and they were never fired against the American troops.

With the success of the original attack, the reserve companies of the 2nd Rangers and the 5th Ranger Battalion were diverted from Pointe du Hoc to the Dog Green section of Omaha Beach and led the assault there–the assault that was memorialized in the movie Saving Private Ryan. Those Rangers who made it off the beach then continued to Pointe du Hoc via land and were tasked with resisting the German counter attacks. It took them two days to reach the 2nd Rangers stuck at Pointe du Hoc.

On the evening of D-Day, the Rangers who made it up the walls did find the guns and destroy them. Then they held their positions on the cliff top for two more days against fierce German counter attacks until they were relieved.

By the end of the battle, only 90 of the 225 men of the 2nd Rangers who had landed were still able to fight. The rest had been killed or wounded.

Here are some photos of the Omaha Beach Cemetery and battlefield. Most of the men killed at Pointe du Hoc are buried there.

Here is another post about our visit to another battlefield of World War II, in Bastogne, Belgium.

Up Your Travel Skills

Looking to book your next trip? Use these resources that are tried and tested by us. First, to get our best travel tips, sign up for our email newsletter. Then, be sure to start your reading with our Resources Page where we highlight all the great travel companies and products that we trust. Travel Accessories: Check out our list of all the accessories we carry to make getting there and being there a lot easier. Credit Cards: See our detailed post on how to choose the right travel rewards credit card for you. Flights: Start finding the very best flight deals by subscribing to Thrifty Traveler. Book your Hotel: Find the best prices on hotels with Booking.com. See all of the gear and books we like in one place on our Amazon shop.Got a comment on this post? Join the conversation on Facebook, Instagram, or Threads and share your thoughts!

Comments are closed.