Table of Contents

Our first mistake

How did we end up on our trek to the lost ruins at the ancient city of El Mirador, one of the most legendary Mayan archaeological sites in the northern Guatemala jungle? Basically, I kind of live by the motto: If you don’t make a colossal screw up now and then, you’re not trying hard enough.

There are a lot of smart people who have said something to that effect. Albert Einstein and Thomas Edison come to mind. However, I’m going to discount their adages a bit because they were talking about mathematical scribbles on a blackboard or maybe burning the wrong filaments in a lab.

I’m talking about walking 120 kilometers through a tropical jungle kind of screw up. Not perhaps as big as Teddy Roosevelt’s The River of Doubt: Theodore Roosevelt's Darkest Journey debacle, but it could have been.

Probably what was the worst thing about it is that Kris and I had at least three clear points when we could have said, “To hell with this,” and headed back to town for a cold one. But no. Even as evidence mounted that that walking through the Guatemalan jungle to an extremely remote location with people we didn't know was a real bad idea, we kept at it. Even a little time into the walk, when it was hot and sunny and dusty and we were parched…and still only about 100 meters into the walk, we looked at each other and said, “How stupid are we?”

The answer was, “Very.”

This is how we got into this.

We have a friend in the travel blogging world (who now owes me big time) who, when he heard we were coming to Guatemala, said, “I’ve always wanted to do the trek into El Mirador. Are you going to do that?”

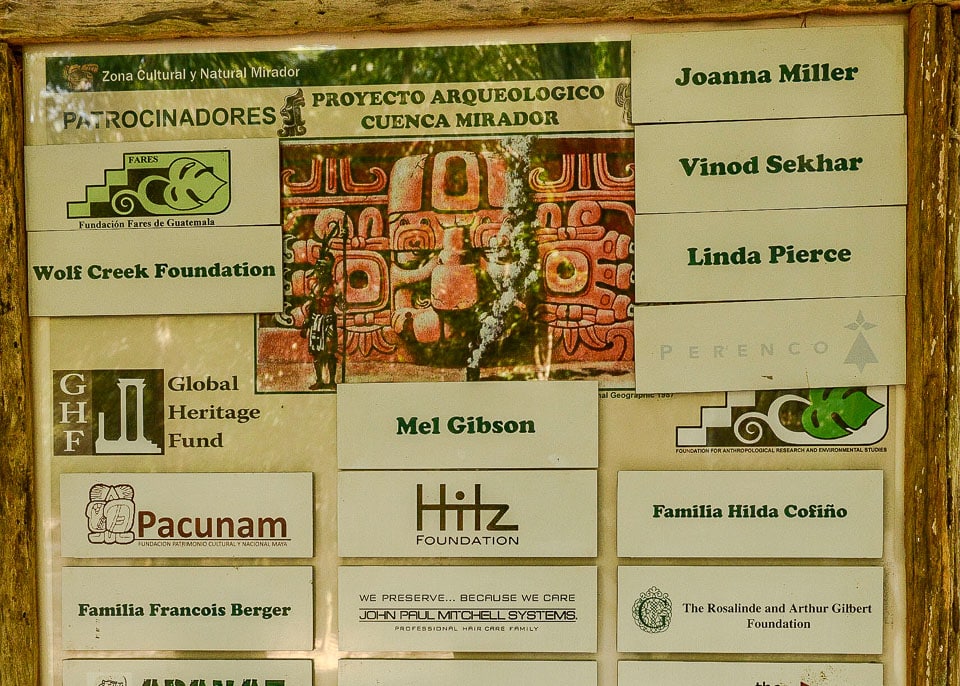

I admit, at that time, I only had a very vague idea of what the ancient Mayan city of El Mirador is. Yeah, I’d heard of it. If you’ve spent any time looking at Mayan historical sites, you probably have, too. But, I went to the trouble to Google it, and ran into some stories that the only way you could get to this cradle of Mayan civilization was by wading neck deep through a swamp for a couple of days. There was no way I was doing that. Mel Gibson, we were told, had visited by helicopter. That didn’t seem all that reasonable, either.

So, I put it out of mind.

When we crossed into Guatemala from Belize, we hired a taxi driver to take us to Tikal, another Mayan site that has been carved out of the jungle and set up quite nicely as a tourist site – with three lodges (replete with howler monkeys as your natural alarm clocks) actually within the grounds of the site. But – and we should have seen this coming – he made a stop at a little shack by the side of the road which arranges tours to various sites in Guatemala. Now we’ve been traveling long enough in various hard scrabble places that we’re very used to – and very capable of – saying, “No, thanks,” in about twenty languages.

But then I saw the poster on the wall. “You do tours to El Mirador?” I asked. “Yes,” he said.

Me: “How do you get to El Mirador?”

“You start from a village called Carmelita, which is about 50 kilometers from here. We’ll take you there in a van. From Carmelita, it’s a two day walk in through the rain forest. You spend a day at El Mirador. Then you walk for two days out. The mules carry all your stuff. All you need is a water bottle, sun screen, and bug repellent. And, there’s one leaving on Friday.” That was the day after we were checking out of the lodge at Tikal National Park, so it fit us perfectly.

Not exactly the definition of what I'd call a “tour” to El Mirador, but, what the hell…

I looked at Kris, and she looked at me, and I could sort of see us both thinking something along the lines of, “We walked for 40 days and 800 kilometers on the Camino de Santiago about a year ago. Spain is hot. We’re not that out of shape yet. We can do this.” We kind of grunted at each other a little bit, shrugged and said, “Ok, why not.”

Decision point one: We hadn’t paid him yet. We didn’t have enough money on us to pay him and he didn’t take a credit card. We could have reconsidered right then.

Nope.

We drove into town, withdrew huge piles of quetzales from every ATM we could find, and turned them over.

We made arrangements to be picked up at 5 a.m. on Friday at our hotel in Flores, after our three days in Tikal. As we were getting back into the car to head on to Tikal, he called out, “Oh, and toilet paper, too.”

Oh, shit.

How we made the same mistake over and over

After our three-day visit to Tikal, we were taken by another taxi Thursday afternoon to a hotel in Flores, where we would be picked up for the van ride to Carmelita and our jungle adventure.

We knew we were getting up early the next morning for our 5 a.m. pickup so we decided to eat an early supper and go to bed to catch up on all that important stuff we do when we have an internet connection.

We were just settling in when we got a call from the front desk. “There’s a guy down here to see you about your tour tomorrow.” So I pulled my pants back on and came downstairs. There was a young man sitting there who started right in in very fast, very accented Guatemalan Spanish, about tomorrow. After I convinced him to slow down a little, he conveyed that we were now being picked up at 4:30 instead of 5. I reiterated my questions: what do we need to bring? And got the same answer: sunscreen, bug repellent, water bottle, and toilet paper. “Anything else we need to know?” I pleaded, knowing that it really couldn’t be that simple. “No,” he said.

Now since we’ve done a fair amount of hiking, we know some other stuff to bring, so we packed some light clothes, our hiking poles, head lamps, my heavy camera equipment, toiletries, etc.

And we went to bed.

We set the alarm for 3:45 so we could shower, finish packing and be ready by 4:30. We were downstairs by then, with two bags each, only to be greeted by the same guy and his partner—on motorbikes.

Decision point. Screw this. I said to him, “We’re not riding on motor bikes to your office to be picked up. If you can’t pick us up here, like you said, we’ll come over to the office and get our money back.”

Damn.

The office was only around the corner. We carried our bags over there where the van was waiting.

Unfortunately, we were the first ones there. “Where are the others?” I asked. “Oh, they’ll be here soon.”

The guy in the office then asked us where we were going after El Mirador. We said, probably Antigua, and he immediately tried to sell us a bus ticket. We not so politely declined.

Just so you know, “Soon,” to the Guatemalans, the Bolivian, the Basques, and the Argentinian who were joining us means, “one hour.” By 5:30, most of us who were going to the jumping off point at the village of Carmelita were in the van and ready to go.

We still had a few stops to make before actually getting fully on the road.

We made one stop to pick up Alex, whose job, as far as I could tell, had something to do with the tour, but in the beginning was just to play Bob Marley at high volume on a homemade Guatemalan boom box. Now, as our small group was complete at nine in our well used Mitsubishi van, including the driver, whose name, as far as I ever learned, was something along the lines of Chooch. The jump seats were installed so we could all cram together and still have room for the luggage and six huge plastic water jugs.

By the way, nine people, plus luggage, plus heavy water jugs, in a van with no seat padding or shock absorbers. Sort of like being on a American Airlines flight.

The air conditioning in the van was also long gone, and since it was about 6 a.m. now and the sun had been up for half an hour, it was about 38 (100F) degrees. So, it wasn’t too bad if the van windows were open and we were moving along.

But, just as we got moving toward the edge of town, we stopped for gas. Now, I’m not going to ask why the van wasn’t filled the night before, but, I have to admit thinking it. After filling the tank, and running around back to rearrange some luggage that had shifted in the three kilometers we’d driven so far, Chooch now backed up a bit to put some air in the left rear tire. More on this later.

Now, finally, I thought, “We’re off.” Not really. We drove another few blocks where we stopped at a market – well, actually more like a shed – so Alex could buy eggs. But this shed didn’t have enough eggs for sale. So we went to another, and then another, until we found someone who had four dozen or so. While we waited for those to be packed up by the chicken farmer, we got out to stretch our legs a bit, because we’d now been in the van for about an hour.

While the eggs were being packed up, Alex bought a cold drink and came back to the van. We all got back in, and so did Alex, until we reminded him that the eggs weren’t actually in the van yet.

It was 6:30, and we hadn’t left town yet.

The actual road to Carmelita

If you can call it a road, which you really shouldn’t.

We were finally on the road, eggs and all, although I didn’t have much faith that the eggs would actually make it to Carmelita, with all the bouncing.

In Mexico and Guatemala there are almost no traffic cops. There aren’t many traffic signs either. What both countries do have in abundance, though, is speed bumps. And, by speed bumps, I mean hard, sharp concrete tank traps at seemingly random spots in the highway where somebody, for some reason, wants you to slow down.

They’re annoying as hell, because they are generally so sharp edged that they don’t really require you to slow down. They require you to stop. Then you can very gradually creep over them, which is the only way to do it if you want to avoid serious damage to your tires, your shocks, your underside, and your passengers.

In Mexico, these speed bumps are called topes, which translates literally as top, and in Guatemala they are túmulos, which is burial mounds, which is sort of apt when you consider what they’re doing to your car. One driver told us that they’re also called policías acostados, which means sleeping policemen. He added that that is the only time Guatemalans get any use out of their police.

What Guatemala also has in abundance, though, is soldiers. They seem to stand around in random places, such as entrances to parks, or crossroads, or little stands they erect by the side of the road so they can look stern while they stop you and give you the once over before sullenly waving you along. I asked the driver why Guatemala seemed to have so many soldiers, but such crappy roads. He said, “The Guatemalan government would rather keep the people afraid than fix the roads.”

Nevertheless, the túmulos and soldiers had been negotiated, and we’d turned off the highway onto the actual road for Carmelita.

And by road, I use the term loosely.

Oh, it was a road, once. But now it was so rutted both horizontally and vertically by traffic and last year's rains that we frequently had to come to a complete stop in order to not break what was left of our suspension system on the ditches that crossed at random, and frequent, intervals. It was if the entire road were one túmulo after another, except these weren't marked by any road signs.

On top of that, the original gravel was long gone. It had long since been pulverized into a very fine white dust. Combine that with the slash and burn farming techniques along most of the road that had reduced the one-time jungle to smoldering dust fields, and you have an idea of what the Oklahoma of The Grapes of Wrath must have looked like in 1934, except it was white instead of red.

So, within about two minutes after hitting the road to Carmelita, everything and everyone in the van was covered with the dust. We couldn’t really close the windows because it was so hot, but, when an oncoming large truck would blow up such a cloud of dust, we did anyway.

Eventually Alex and one of the Basques decided that it would be cooler to just get out of the van and ride on top. Which they did. Between clouds of dust, I could see their shadows on the white dust road and wondered if they also liked to jump out of airplanes without a parachute, or at least ride motocross bikes without a helmet.

Sometimes, Chooch had to stop the van entirely, not because of a rut, but because he had to wait a minute for the dust to settle so he could see the next rut.

Then it got a bit better. After an hour and a half of rut surfing, the road changed from the deep dust to a more solid, albeit rocky road. It was still very bumpy, but not as ditchy. Unfortunately, the rocks were sharp. Like the rocks Mayas had chipped away at to make axe blades sort of sharp.

Remember that tire we filled back in town? Boom. Now it was flat.

And, while we had a jack, it wasn’t the “right” jack. It wouldn’t lift the van high enough off the ground to get the flat tire off.

Here, though, is where we learn some Guatemalan ingenuity. All you have to do is find a big enough rock, drive the flat tire onto that rock. Put another rock under the jack to get the van's axle high enough, then kick the rock out from under the tire. That took a couple of tries, because when you’re kicking one rock, it sort of tends to move the whole van, and it’s a 50-50 proposition which is going to happen first. Is the rock going to come out from under the tire, or is the jack going to tip off the other rock, crashing the van back down on the flat – which necessitates repeating the process?

Guess which happened.

Finally, though, the tire was fixed, and the spare was attached. The spare, by the way, was very low on air as well, but, thankfully, it did get us into Carmelita.

We actually start walking

We didn't start out from Carmelita right away, mind you. First there were plates of beans to be eaten and mules to be packed.

In general, we love what we’re doing, and don’t mind so much the “travel days” when we actually have to schlep bags to a train station or airport and give up the comfort of a hotel room for the discomfort of actually moving.

But nothing like this.

We’ve done some hiking. We’ve walked in the Minnesota North Woods. We’ve hiked in the Grand Tetons. We did the Camino de Santiago – 800 kilometers worth of Spanish heat, punctuated by climbing mountains made of broken rock – but something was telling me all along that this was going to be only one seventh as long, but seven times worse.

I need to listen to myself more often.

After the three-hour coccyx-smashing ride in the Mitsubishi van from hell, we finally arrived in the village of Carmelita. As far as I could tell, Carmelita exists solely to provide a jumping off point for El Mirador. (I later learned this was essentially true.) It’s a small village of about 300 residents, and most of the adults take turns as local guides leading expeditions into the various Mayan sites, and/or serving the tourists’ supply needs before and after the trek.

As we arrived and unloaded our packs from the van, we were not told what we were expected to carry ourselves, and what the mules would carry for us.

This was important information, because we didn’t actually ever walk alongside the mules. They were either way behind (at the beginning) or way ahead (a little while after we got going.) So, if you put something on the mules that you would need on the trail, you were out of luck. Or, if you carried something you wouldn’t need on the trail, you were, in a word, dumber than the mules.

Just call me Dumb Ass.

Since I photograph almost everything we do, I chose to carry my heavy photo backpack. Although I’d emptied it of everything except the actual camera and lenses, the thing still weighs far too much. Let’s face it: metal and glass are heavy. And, the sturdy tripod. Add to this a bladder system with three liters of water, and I was probably carrying more weight than I’d carried on the Camino.

But, we weren’t quite ready to start yet. First, there were beans.

You may have noticed that, except for Alex’s egg adventure, I haven’t mentioned food yet. That’s because there hasn’t been any. It’s nearly 11 a.m. We’ve been up since before dawn. And we haven’t had so much as a coffee. Or water.

But, we had been promised breakfast, and after piling our packs into people stacks and mule stacks, we were invited to the other side of the village to the “dining hall.” We walked over the sun-baked pasture where the mules were grazing to another complex of shacks and were directed inside past the kitchen to a couple of rough tables and wooden benches.

What better way to satisfy that peckish feeling than a big plate of scrambled eggs and refried beans? I like eggs and beans as much as the next guy, but a late morning brunch of what is basically a plate of lard is probably not the most settling idea for someone like me who generally has a bowl of bran flakes and maybe a piece of toast. But, by now, I was very hungry and my appetite got the best of me. I ate it all and washed it down with two big cups of strong coffee.

Like I said, just call me Dumb Ass.

We sat around and talked for a little while before a heretofore unknown woman came into the dining area, introduced herself as Maria, and told us it was time to go. So, we dragged our newly fed and bloated selves back over to the other side of the village where the mules were already packed – in my case, carrying my light little day pack with a couple changes of clothes and a toothbrush – and leaving enough camera equipment to shoot Lawrence of Arabia for me to carry.

We set off.

I’ve mentioned that this was a jungle hike, but we weren’t actually there yet. After walking out of the village, which took about two minutes, we came to a dusty road much like the one we’d driven in on. And it was now noon. The sun was directly overhead. It was about 40 degrees (104F) in the shade. And there wasn’t any shade.

We walked along this road for about a kilometer before taking a right turn into what was, comparatively, the jungle. By this time, I was thinking, repeatedly, “I should turn back. This is nuts.” But, I didn’t.

Dumb Ass.

We walked through a wooded area. But I soon realized that it wasn’t what I’d call a jungle. There were no trees taller than about five meters, and certainly no overarching canopy that provided any shade. In fact, trees as high as even that were very rare and very scraggly and thin. As I peered deeper into the wood, I could see evidence of two things: stumps and fire. This place had been recently clear cut and burned off by farmers. Yes, they’d abandoned it a few years back, but the forest hadn’t recovered and we were walking without shade for as far as I could see ahead.

But that wasn’t the worst of it. Soon we got off the usual broken limestone base and got into an area that actually had some top soil. But here, too, was evidence of a stuff Americans usually only read about in earnest articles in liberal magazines. Here once was a tropical forest of cedar and mahogany. Now, what you could see was a deeply rutted road where the trucks had come into the area during the rainy season to haul out the timber.

Instead of a smooth leaf strewn path there were deep tire-plowed furrows of mud that had been baked into black brick by the unbroken sun. That provided a walking surface that reminded me of walking across stepping stones in a brook. You had to look for flat patches among the ruts to place each step, and good luck finding a level one that wouldn’t send your ankle bending and sliding into the rut. Sometimes it was easier to just walk in the rut. Sometimes it was better to walk on the frozen waves of mud thrown up on the side of the rut. Either way, it was slow, and treacherous, and clumsy, and hot, and miserable. Even more so since I was stupidly carrying the camera bag because I thought there would be something beautiful along the way I’d want to photograph.

This went on for more than two hours before we finally reached the actual jungle.

Of course, by that time, I was courting heat exhaustion, I had more gas than Exxon-Mobil, and the rest of our small group was a long way ahead of me. And our stopping point for the day, El Tintal, was still twenty kilometers ahead.

Praying for help

As I was staggering in the heat toward El Mirador, I thought back to a couple of hours earlier when Maria had stopped us all about ten minutes into the walk. She had gathered us in a circle, asked us all to bow our heads, and then offered a rather long prayer to Jesus to protect us and guide us in our walk into the jungle.

“Jesus?” I thought at the time. “I have to rely on Jesus? I thought that’s what Maria and Eric were for.”

I should probably take this opportunity to introduce Eric, the man who saved my life. Well, not exactly, but it sure felt like it at the time.

Eric is Maria’s 22-year-old son and it was actually he who was our titular guide. (We also learned somewhere along the way that Alex the Eggman was Eric’s older brother. But, since Alex had married an American girl who had a good job in Flores, he didn’t actually have to do the hard work of guiding any more. Alex’s job, evidently, was playing reggae and buying eggs. I’ve often advised my own son that the key to life was to marry a rich woman, so I couldn’t exactly fault Alex for his choice.)

Eric had a perpetual sort of goofy smile on his face. Not that he was goofy, mind you. It’s just that he was good-natured. Which was a really good deal for all of us, because his guiding equipment consisted mostly of a very big and very sharp machete which hung off the left side of his belt, and a very big and very sharp KA-Bar knife which hung on the right side. When I motioned at the knife once, his only comment was, “I’m Rambo.” And a big smile.

Thank you, Jesus.

This is just background. Now we pick up where we left off, still 20 kilometers from our scheduled stopping point. It’s over 100 degrees. There’s no shade. I’m carrying way too much crap. And I’ve dropped a few hundred meters behind the rest of the gang. I stopped, sat on a log, sucked some water out of my hydration tube, spit it into my hands and splashed it over my face and neck. It was warm water, by the way.

I wasn’t going to die anytime soon, but I was beginning to wonder if a massive stroke wouldn’t be better than being slowly parboiled in my own sweat and self pity.

Hell, I was even thinking of calling out to Jesus myself. Or at least to a Mayan feathered serpent god since it seemed to me that he might be closer at hand. But I’d be damned if I could remember the fluffy snake’s name. I was bent over, looking at the ground and praying for a little breeze from Aeolus, the Roman god of wind whose name I could remember from my Latin studies. I was working hard to remember some Latin incantation that I hoped he’d answer.

That’s when Eric showed up.

He’d walked up so quietly that I hadn’t heard him. So he had to stick his face right down next to me and ask, “Are you ok?”

Scared the shit out of me.

After recovering, and fanning myself for a few seconds with my hat – which is a poor excuse for a Roman god, by the way – I said, “Well, you could talk me into tossing $7,000 worth of camera gear into the jungle.”

“Why don’t you let me carry it for a while?” he offered. “We’re only an hour from our rest point, and we can put it on the mules when we get there.”

Since he was already carrying a backpack full of our food for the day, and his own water, I said, “No, I can carry it.”

I’m sort of stupid that way.

“No,” he smiled in a very nice way and touched his knife. “It will be faster if I carry it, and it’s only for an hour.” What he left unsaid was, “I’m young and fit and used to the heat – and you are the opposite of all those things.”

So, I let him carry my camera bag. I did bravely carry on with my own water though, since I didn’t want to have to stop him and beg for it every two minutes. I took the bladder out of the camera pack, dropped it into the wide thigh pocket of my hiking pants, hooked the bladder cord around my belt, and started walking alongside Eric.

Of course, I had to stop and figure out an adjustment after about ten steps, because the two liters of water was heavy, and the combination of the bladder pulling and my belly pushing was sending the waist band of my pants down around my knees, which makes it sort of hard to walk.

Did I mention yet that I really hated my shoes, too?

Never wear waterproof shoes

So Eric and I walked along toward El Mirador. And except for constantly hiking up my pants which were still being tugged down by the water bladder, things were going much better. Soon after he relieved me of my camera bag, the path became a lot smoother – packed soil strewn with leaves mostly.

And we soon arrived at a bit of a clearing where the others were sitting waiting for us. We were halfway to our stopping place for the night, and they were all happy to see Eric, because Eric was carrying our snack: a couple of ripe papayas.

He took them out of his own backpack, placed them on a split log and used his huge knife to slice them into strips which he distributed to us all. Sweet welcome refreshment as we sucked the pulp off the rinds and then joyously tossed them into the jungle.

Since Eric and I had arrived at the clearing about 20 minutes after the others, we didn’t get as much rest. Although he was relieved of the heavy papayas, as well as my cameras that finally found their way onto the mules, we didn’t have long to rest before Maria herded us back onto the path.

I did have time though to take off my shoes and socks though and have a look at my feet. As I mentioned earlier, I hated my shoes. When we were last home in Minnesota, I’d dropped into a Columbia gear store where they were having a sale on trail shoes. I had a perfectly good pair of Adidas trail shoes that I was planning on taking on this trip, but because after hot dry Central America, we were planning to hike in cold, wet northern England and Ireland, I bought myself a pair of waterproof trail shoes.

I asked the clerk, “How do these shoes breathe and dissipate heat?”

“Just fine,” she said. “It’s a breathable technology.”

Now, I should have been smart enough to know that waterproof means dry on the outside, soggy on the inside. That’s the way my so-called breathable Columbia rain jacket is, anyway. And, yup, that’s just how the shoes worked, too.

And since I was concerned about weight, I only brought the Columbia shoes and not the nice light breathable Adidas trail shoes. I’d worn the waterproof shoes a lot on day walks in Mexico and thought I’d broken them in alright. And, while I noticed that they were indeed somewhat hot, I thought they’d do.

Like I said, I hated them.

When I pulled off my shoes and gingerly peeled off my socks in the clearing, what I feared – and had been feeling – was quite obvious. I already had a big blister on the outside of each heel and under two or three toes of each foot. And, my dry socks and foot powder were packed somewhere under a ton of provisions on one of four mules.

And, although I’d even once written an entire blog post about foot care on the Camino de Santiago, I had been too stupid to remember my own advice.

So, I put my sweaty wet socks back on. Carefully pulled on my hard, impermeable, agony shoes. Laced them up tight, which kind of hurt for the moment, but I hoped that they wouldn’t rub so much as we continued, and headed off again.

Blisters aren’t really too bad. They’re more of an annoyance than a real pain. But, you do notice and compensate for them and change your gait. That’s when your hips, knees and back begin to remind you what an idiot you are. And make you stop every ten minutes or so to stretch or otherwise contort your stiffening muscles – muscles which actually are hurting more than your feet – at least so far.

Oh well.

Finally, at about 5:30, and only about 10 minutes behind the others, Eric walked and I limped into the camp at Tintal, which is another Mayan archeological site that is being infrequently and desultorily worked. The actual ruins were a little ways away from the camp ground. The campground was a fairly large clearing where a permanent structure to house an exhibition and provide a roof and a veranda for visitors had been constructed…and then abandoned.

There was a open walled structure with a plastic tarp roof which contained a rough picnic table and flat benches and a couple of logs to sit on. There was also a heavy table on top of which was arranged a rectangle of stone with one open side which provided the support for a metal grate and/or a tray. This was our cook stove. Along side it at a right angle was another similar stove that was just a bit smaller.

By the time Eric and I arrived, Maria already had fires going in both. Stewed chicken, rice, and, yum, more beans.

And, since the stoves were right by the eating tables, we would be nice and toasty while we ate.

Anyway, the rest of the troop went off to see the El Tintal ruins, another half hour walk away, but I fished my blister repair kit and foot powder out of my pack which had now been liberated from the mules, took care of my feet, and sat around and drank jungle tea and talked to Maria.

She told me that my problem was “city feet.” I already knew that. She said she had “country feet.” Which she did. She’d walked the entire way from Carmelita in flip flops.

I set a goal for myself. When I got back to civilization, I was going to toss those Columbia “breathable” shoes in the nearest trash bin.

Bees

It's not that we were attacked by killer jungle bees at Tintal. We weren't. But at first glance it seemed possible.

Let me explain.

Since the clearing at El Tintal where we were camping was the only place for miles around with any water, the bees had come there, just as we had, to get a drink. It was nice that the two guys who were manning the Tintal clearing hauled the water on mules from an hour and a half away. The bees thought so too, although they weren't paying for it like we were.

The water purification process used in the Guatemalan hinterlands is a system of five gallon (or thereabouts) buckets stacked one on top of another. You pour water into the top one, and it passes through a filter of some sort, very slowly, into another bucket. You then pour that bucket’s contents into yet another top bucket that drips the water through a different filter. Repeat the process one more time and you have potable water. It’s warm and tastes terrible, but you can drink it.

Of course, the bees don’t need to wait for the filtration. They just congregate by the hundreds around every dripping bucket and hover, dive in, sit on the edge and sip, or whatever strikes their fancy. What that means, though, for us, is that 1) there are a million bees all over the camp; and 2) if you want a drink of water, you have to nicely ask the bees to move over so you can access the spigot on the bottom of the final bucket.

Now, I like bees as much as the next guy, but maybe not in such volume and proximity. I soon learned that even if you were kindly afforded access to the bees’ water source, if you took a glass of water away from the buckets over to some shade to drink it, you were bound to soon have some apian company who wanted to share.

It wasn’t so bad, though, although it was a little disconcerting to realize that if for some reason the bees got pissed off, you were probably going to be really sorry. But, in the end, only Maria got stung once, which she just shrugged off after using Eric’s razor sharp Rambo knife to scrap the stinger out of the back of her hand.

While the other intrepid hikers walked off into the jungle to visit the Tintal ruins, Maria and I again sat around the cook stove because the smoke from the wood fire kept the bees at a respectful distance. As the elder statespeople of the group, we traded folk wisdom over some jungle tea that she made from leaves she’d harvested along the path. I talked to her a bit about my theories of story telling (the more bullshit the better) and she responded with a couple of questions:

“Do you know why I drink this tea?” she asked.

“No, I don’t,” I answered, expecting some sort of ancient Mayan wisdom.

“Because I’m thirsty.”

Well, that was disappointing.

A minute later, she moved the eggs she’d just cooked from the table back toward the fire. She asked, “Do you know why I’m doing this?”

Again, expecting profundity, I got instead, “To keep them warm.”

I immediately asked her, “Why did the chicken cross the road?” But I don’t think they have that joke in Guatemala.

Kris and I had another close encounter with the bees a bit later, when we learned that the guys who were manning the clearing would sell us a bucket of water for a shower for 20 quetzales – about $3. And, because Kris and I could take the bucket shower together, we’d get a two for one.

So, we went over to the plastic covered stick enclosure. The guy brought us a bucket and a little bowl to dip the water and splash it over ourselves, and we undressed and began to rinse and soap up. For the first time in the hike, I’m glad the water was “room temperature,” that is, about 35 degrees C (100 F) just like the air around us.

Very soon, though, we were joined by about 50 bees who had decided that, hey, water was water, and they could use a dip as well. Kris, I and the bees all agreed to ignore each other and I poured water over Kris and she did the same to me, and the bees didn’t mind being splashed so much that they got angry about it and we all came out clean and refreshed.

And, in our case, ready for bed. It was about 8 p.m. and still light, but we were exhausted and full of Maria’s dinner and sugary tea. So Kris and I limped off to our tent to get ready for a sweaty night on very hard ground.

It turns out, though, that the mules hadn’t only been carrying water. The “youngsters” in the group, i.e. the two Basques, the Guatemalan, the Bolivian, and Eric – dug into a pack and came up with a couple of bottles of Guatemalan grain alcohol. And since the Basques had also brought along an ample supply of what smelled like really good marijuana, their party was only getting started.

They pretty much kept us awake until 1 a.m. of so, until the booze ran out, and our hopes of an early start in the cool of the morning were shattered.

Although Kris and I got up with the loud birds at five, the rest didn’t roll out until about eight. We had an early breakfast with Maria, and all sort of shook our heads at the children.

We reach El Mirador – finally

I started out right on the next day, except I was still wearing the hard sweaty shoes and was limping out of the gate on some big blisters. However, we were now in deep jungle and that meant shade, if also no breeze, high humidity, and since the sun was well up by the time we started, high heat.

But at least I wasn’t carrying much. A light day pack that just had my 3-liter water bladder, an extra pair of socks, foot powder, and a roll of toilet paper. You never know when you’ll need the last item.

I think because he was hungover a bit, but also because he still felt he needed to keep an eye on me, Eric matched my pace for the most part. He could see I was in some pain, and he encouraged me all along the way with a report of how long it was to the next rest stop. It didn’t take me more than two or three such predictions though, to realize he was intentionally giving me false hope. If he told me it was an hour to a rest, it was an hour and a half. If he said two hours to El Mirador, it was three.

He thought he was doing me a favor. And I suppose he was, in a way, by just reminding me at all that there was a cool clearing out there somewhere with my name on it. I would have liked it better if the clearing had been next to a cold running brook I could have soaked my feet in, but I guess we should have waited for the rainy season to make our trek into El Mirador.

We stopped once in the morning for a 10-minute break, with more papayas. I wasn’t ready to change socks yet as I’d only brought one extra pair today. So i just pulled them off and filled them with foot powder and pulled them back on. Gingerly.

Two hours later we stopped for about an hour for a lunch. I didn’t mention the first day’s lunch, but this was exactly the same: Pan Bimbo, which is the Latin American equivalent of the most insipid supermarket brand of over processed white bread you can imagine, and boiled lunch meat and cheese slices. And mayonnaise.

In other words, the exact same sack lunch my mother sent me off to school with for seven years of my life, minus the five cent bag of Fritos and a couple of Hydrox cookies.

Thus fortified, and after another series of Eric’s time shifts, we made it into El Mirador’s clearing around five. All in all, we were told it would take six hours, but it was closer to eight. I hobbled in only about ten minutes behind the main group, but I attribute that to the fact that, being behind the mules all day meant I had to watch out not only for snakes but also mule shit.

The clearing where we were camping had been a plaza in the old enormous Mayan city. It was approximately a hundred meters square and was bounded by remnants of Mayan walls. It had been assiduously cleared. Maria told us this is where the archaeologist Richard Hansen, who is in charge of the site, landed when he came in by helicopter. And Mel Gibson, too, I bet.

Richard and Mel are wimps.

Maria continued, somewhat disdainfully, that Hansen had a house up on the hill with all the modern conveniences, including electricity from a generator that ran, among other things, air conditioning and a refrigerator. Again, according to Maria, the house is decorated with scads of artifacts Hanson has picked up in his years of digging. And, he uses the house to entertain wealthy donors who also helicopter in to see where their money is going.

I don’t see much wrong with that, really. If they guy lives half the year here in this dirt and heat, he deserves some break and to surround himself with the artifacts of the cultural heritage he's been responsible for unearthing. And, it’s not like he hasn’t been working, as we’ll see tomorrow when we explore the site.

Nevertheless, the resentment from Maria was unmistakable as she began to cook our dinner.

As she prepared our beans and rice, Eric and Tono, the mule driver, began to pitch the tents under the permanent black plastic tarps that were strung between trees. It wasn’t long before we noticed that there were only two larger tents, instead of the three smaller ones we’d had at Tintal.

We didn’t know it at the time, but the tents at Tintal were sort of communal tents that all groups used. The ones Eric and Tono were setting up were the ones they’d brought along because El Mirador doesn’t have anyone there to look after the equipment like Tintal does. And, we were told that Kris and I would be bunking in with Simon and Ana Maria, the other couple.

To hell with that.

Well, it got sorted out eventually when we decided to use a tent of another group that was a day (maybe two) behind us and that was pitched and left in another area of the camp. Since we were going to be at El Mirador for two nights, we hoped the latter.

So, we had our own tent. We asked Eric to pitch it in the clearing so we could get some breeze, but he said he had to put it under the tarps to protect the tent.

This concept that it was more important to protect the already worn tent than provide for the comfort of his clients was not unfamiliar to me. “Third World Thinking” is how I describe it. It honestly wouldn’t occur to him that people like his seven clients (who, btw, were a doctor, two engineers who worked for a high tech company in Germany, two guys who could afford expensive dope, and two successful entrepreneurs,) wouldn’t think twice about kicking in $200 to buy him a new tent if it came to that.

So Eric had no idea that I actually was serious when I offered him $200 to buy a new tent when we got back to town. But I was. I even had it with me.

I was that desperate for a breeze.

But, I might as well have been speaking Mandarin, and we ended up under the tarp sauna again.

The day at El Mirador

Kris and I got up early the next morning, mostly courtesy of a wild turkey who was squawking his way back and forth across the clearing. They really do make a sound that could be called a “gobble,” by the way.

We’d been promised a dawn hike to the La Danta pyramid. La Danta, is within El Mirador and is considered the world’s largest pyramid by volume. I hoped to get some photos of the dawn, presumably the best time to get a view over the Mayan city, but that of course wasn’t happening, again due to the effects of various nightcaps, I presumed.

So, I grabbed my camera and tripod and hiked off into the jungle by myself in the direction that Eric had indicated to me the night before. I walked along barely cleared paths, past various dump sites of archeological detritus such as broken tools, wheelbarrows, and empty sacks of concrete. I continued on this path for a while as the sun climbed, ruining any possibility of a shot of the pyramid framed in the light of the rosy fingered dawn. I kept going as long as I felt comfortable that I could find my way back – about 45 minutes – and until I was sure that I’d somehow missed the right trail on this huge site.

I turned around and made it back to camp about the time the others were waking up. Maria was brewing some jungle tea which she offered to me. “Where have you been?” she asked.

I pointed down the hill where Eric had indicated to me lay the great pyramid and said, “I walked down there looking for the pyramid so I could get a picture at dawn, but I couldn’t find it,” I said.

“That’s because it’s over there,” she said, pointing off at a 90 degree angle to the path I’d taken. I looked over at Eric, who was rubbing the sleep from his eyes as he pulled on his shirt. “Didn’t you tell me it was that way last night?” I asked him.

“Yeah, but I guess I wasn’t really paying attention last night. But, we’ll all go as soon as we’ve eaten.”

Oh well, what’s an hour and a half fruitless hike in the jungle when you’re having fun?

The temple did indeed turn out to be in the other direction, and we all hiked off after breakfast. At least I’d had the distance right. It took us 45 minutes to get there. And another several to climb the the wooden stairway built up its side. This stairway and some roughly cleared paths were the only conveniences for us tourists that had been provided anywhere on the El Mirador site.

And, of course, they aren’t really tourist conveniences. They are constructs built by the diggers for their own use to move themselves and their equipment to the disparate sites where they are working. Because, if it hasn’t been clear from the beginning, this isn’t a tour like the ones you take at Chichén Itzá or even Tikal. El Mirador is not a tourist site. It’s an archeological dig in progress that reluctantly tolerates people like us who walk in for two days and then beat it out of there, essentially leaving little trace they were there.

There are very few didactic signs and precious few signposts. The tour relies on people like Eric, who turned out to be an excellent guide full of knowledge about the site, the work, and most interesting, the Mayan mythical figures depicted.

So we climbed the pyramid, and wandered around a few other dig sites where we were able to see, at some distance, remarkable carvings that had been uncovered. Unfortunately, like I said, at a distance, because, since there was no curation or guard in place, wooden barricades had been erected around pretty much everything you’d have liked to get a good look at. The closest we could get to looking at pristine thousand-year-old carvings depicting the Mayan creation myths was about 10 meters, and since they were down in pit that had been shaded by more of the ubiquitous black plastic tarp, it was a dim look at that.

Therefore, my advice is if you want a good look at what El Mirador has to offer, call Richard Hansen and ask him for a job. Otherwise you’re not getting close to much of it.

This revelation engendered some discussion at lunch when we got back to camp. Carlos the Argentine opined that the people running this place were really stupid not to build a museum somewhere on the grounds to display all the cool stuff they were undoubtedly unearthing.

Well, since I hadn’t been in an argument other than with my feet for a couple of days, I casually said, “Who would be stupid enough to walk through the jungle 56 kilometers each way to see some broken pots?”

“Other than us?” I continued.

But I didn’t say that last part out loud.

Back to Carmelita

The gang went out again to see more things after lunch, but, since I’d already had an hour and a half hike that the others missed, I listened to my blisters and skipped it.

Honestly, I should have gone, but I was exhausted. Moreover, because of the disappointment of both morning hikes, I’d stupidly developed an attitude that could best be described as “pre-disgusted.”

So, I thought I’d save myself the trouble and hang back and talk to Maria, Tono, and the mules.

But, Tono’s accent was totally incomprehensible, the mules were busy eating, and Maria was cleaning up after lunch and raising an enormous cloud of dust by, believe it or not, sweeping the leaves from the area with a broom she’d made from some branches she cut.

Sweeping the jungle. Now I’d seen everything.

So, I rolled a log over under a tree, got out my notepad and made some notes.

Here they are – at least some of the random ones that I didn’t work into the narrative.

Maria cooked up fried Spam and eggs for breakfast our first morning in El Mirador. I told her that Spam was made in my home state of Minnesota, and I thought it was funny that I had to come to the jungle of Guatemala to eat it for the first time in my life. She couldn't believe I hadn't had Spam before. BTW, after I took one look at it, I still have yet to eat Spam for the first time in my life.

Sometimes when he’d not leading tours, Eric works at El Mirador as a digger. It’s one of the reasons he knows so much of what is there.

Every evening Eric and Tono would scale tall Ramón (Hackberry) trees with their machetes to cut leaves for the mules' feed. Sometimes Eric used spikes strapped onto his boots to run up the trunk. Sometimes, he just did it without.

The mules’ names, according to Eric, were Cara Sucia (Dirty Face,) La Peruana (The Peruvian Girl,) Checha, and No Me Acuerdo (I Don’t Remember.)

A shower at Mirador can be purchased for only 10 quetzales from the site workers, as opposed to 20 quetzales in Tintal. The water is closer to El Mirador and they have ATVs in addition to mules. Of course the discount could also be due to the fact that the shower enclosure (and the outhouse) had to be shared with bats.

One of the bats gave Cara Sucia a hell of a bite on her neck the night before we left El Mirador. Blood had run down her neck and the puncture wounds were obvious. I hoped she wouldn’t turn into a vampire on the way home. I also wondered if mules are subject to rabies.

At several places along the path in and out of El Mirador, you can see where thieves have burrowed into Mayan walls to steal artifacts. There’s no way to stop them, and some of their digs are very recent. Guatemala doesn’t have the inclination or resources to stop them this far out in the jungle.

Maria is one of the founders of the cooperative at Carmelita that runs the expeditions into El Mirador and other sites in the jungle of Petán Province. Leading these tours is almost the only source of outside income for the village of Carmelita.

Recently a big national tour operator, with the help of the government and army which administrate the remote and poor province of Petán, has forced its way in and threatened the people of Carmelita with, shall we say, harsh consequences if they don’t turn over a large percentage of the tour fees to them.

As a result, the fees to the tourists have gone up while the pay for the people of Carmelita has declined. Maria told me the tour company pays for the mule driver, the food, the water, and the equipment for the tour, so she doesn’t have to organize that. In total, the seven of us tourists paid $3500, or $700 each, for the tour. Eric, who was the “guide,” got paid the equivalent of $130 for five days hard work. Maria, who was the “cook,” got paid $100. Tono the mule driver got less. You can do the math, but this leaves the tour operator with a gross profit of $3200 with which to buy the food. I told you what the food was like.

So, if you decide to try El Mirador in spite of all you’ve read, try to figure out how you can deal directly with the folks in Carmelita. That won’t be easy unless you find your way out there by yourself and are willing to wait a couple of days there while your tour gets organized. This is no small undertaking, and you don’t want to be out there unprepared or with people who don’t know what they’re doing.

Eric and Maria both absolutely knew what they were doing. They both have a profound knowledge of the jungle and will give you a running lecture of the flora and fauna, the Mayan myths, and any other questions you might ask them. Neither of them has ever been outside of their province in their lives. In fact, they’ve rarely been out of Carmelita and its surrounds.

Eric’s father, Maria’s former husband, was murdered by his employer who owed him a sum of money. Since the banks aren’t the best in Guatemala, he’d asked the employer to withhold some of his wages every month as a “savings” plan that he intended to use for Eric and his brothers. When he asked the employer for the money, she hired someone to kill him so she wouldn’t have to pay him. The amount in question was less than $3000 USD. Eric told me this story on day one as we were lagging far behind the group. He didn’t tell anyone else. He told me that some day he would track down this person. He had an idea where she might be.

When I asked him if the police had tried to solve his father’s murder, he just laughed.

When we finally arrived back at Carmelita early afternoon of day five (we’d finally got that early start out of Tintal on the last day,) Kris and I were this time only a few minutes behind the rest of the group. As we walked into town, Maria rushed out of the hut at the end of town and welcomed us back to civilization with a warm glass of syrupy orange drink. How could I tell her that I just can’t drink stuff like that? So I waited until she turned her back and dumped it on the dirt floor of the hut, behind the stump stool so she wouldn’t see it.

The good folk of Carmelita fed us a lunch of roast chicken and rice before we climbed back into the van for the ride back to Flores. Miraculously, the good folk or Carmelita were also able to produce cold beers for us all, although they charged us the equivalent of about 30 cents each for them. I had two. So did Kris.

The ride back to Flores was even dustier and bumpier than the ride in. There were a lot of big trucks on the road, and they were making a lot of dust clouds. We closed the van windows and held our breath as long as we could.

The night we got back to Flores. Kris and I checked into our hotel and immediately went to search for a bar. We found a great one right on the lakeside and mojitos were on special for about a buck. I think we each had 12, and that’s no exaggeration. We were there for a long time.

While we were there, power to the area was cut, so the fans that provided a basic breeze on the veranda were useless. However, as we sat there from late afternoon to mid evening, the much anticipated rainy season arrived. A big breeze came up, clouds closed in over the lake, and a tropical downpour soaked the city up to everyone’s ankles.

It was paradise.

Postscript: To amuse myself while walking I had written a couple haikus in my head. I dictated one of them to Kris our second night in El Mirador. I’d forgotten all about it until she pulled out her notebook and reminded me. Here it is.

El Mirador trek

Dusty forest to nowhere

Never going back.

Here’s another one though. After some reflection.

Blisters are small price

for new insight and story

You should do it too.

Note: We did our trek to El Mirador, Guatemala in 2013. This is an edited version of the 10 posts I did at the time.

Here's a little history of El Mirador from Wikipedia: El Mirador flourished from the 6th century BCE to the 1st century CE, reaching its height from the 3rd century BCE. Then it experienced a hiatus of construction and perhaps abandonment for generations, followed by re-occupation and further construction. It was finally abandoned at the end of the 9th century. The civic center of the site covers some 10 square miles (26 km2) with several thousand structures, including monumental architecture from 10 to 72 meters high.And here is a story from the BBC on recent discoveries of Mayan civilization in Guatemala.

FAQ questions and answers about El Mirador

What is El Mirador?

El Mirador is a pre-Columbian Maya civilization archaeological site located in the Mirador Basin in the far northern part of the province of Guatemala. It was one of the largest and earliest urban centers of the ancient Maya civilization, believed to have been founded around the 6th century BCE and inhabited until the 1st century CE.

Where is El Mirador located?

El Mirador is situated in the Mirador Basin, located in the northern region of Petén in Guatemala, near the border with Mexico. It's situated within the dense jungles of the Maya Biosphere Reserve.

How can I visit El Mirador?

To visit El Mirador, one would generally have to join a guided tour, which can be organized through various travel agencies in Flores, Guatemala. The journey to El Mirador is usually undertaken on foot or mule due to its remote location, and it's part of a multi-day trekking expedition.

What are the prominent structures at El Mirador?

El Mirador is home to several significant structures, including La Danta, one of the largest pyramids by volume in the world. Other notable structures include El Tigre, Los Monos, and La Pava. These structures feature complex facades and artwork, providing insights into the ancient Maya civilization.

Can I explore the site on my own?

Due to the remote location and the preservation efforts in place, independent exploration of El Mirador is not recommended. Visitors are encouraged to join guided tours which not only provide safe access to the site but also offer insights and information about the history and significance of the ruins.

What is the best time to visit El Mirador?

The best time to visit El Mirador is during the dry season, which is from November to April. During this time, the trails are more accessible, and the weather is generally more favorable for trekking.

What should I bring on a trek to El Mirador?

When trekking to El Mirador, it's essential to be well-prepared. You should bring comfortable hiking shoes, light but long clothing to protect against insects, a hat, sunscreen, and a sufficient supply of water. Obviously, a camera to capture the breathtaking sights is recommended.

What kind of wildlife can I encounter in the region?

The region surrounding El Mirador is rich in biodiversity. You might encounter various species of birds, monkeys, and possibly even jaguars. The area is also home to a wide range of flora and fauna endemic to the region.

What research and conservation efforts are ongoing at El Mirador?

El Mirador is a focal point for archaeological research, with several organizations and universities involved in ongoing excavation and conservation projects. Efforts are also underway to preserve the site and its surrounding environment from deforestation and looting.

Are there any accommodations near El Mirador?

Due to its remote location, there are no traditional accommodations near El Mirador. Visitors usually camp at designated areas during their trek, with tents and basic amenities provided as part of guided tours. Planning and booking with a reliable tour operator is crucial for a comfortable experience.

Up Your Travel Skills

Looking to book your next trip? Use these resources that are tried and tested by us. First, to get our best travel tips, sign up for our email newsletter. Then, be sure to start your reading with our Resources Page where we highlight all the great travel companies and products that we trust. Travel Accessories: Check out our list of all the accessories we carry to make getting there and being there a lot easier. Credit Cards: See our detailed post on how to choose the right travel rewards credit card for you. Flights: Start finding the very best flight deals by subscribing to Thrifty Traveler. Book your Hotel: Find the best prices on hotels with Booking.com. See all of the gear and books we like in one place on our Amazon shop.Got a comment on this post? Join the conversation on Facebook, Instagram, or Threads and share your thoughts!

Comments are closed.